Australians on the Somme

1st Australian Division Memorial, Pozières

The village of Pozières sits on a ridge in the centre of the Somme battlefield. As such it was a heavily fortified important German offensive position. On the 22nd-23rd July it was attacked by the 1st Australian Division. Preceded by an artillery bombardment which included both phosgene and tear gas the infantry crept into no man’s land and attacked as soon as the barrage was lifted. Hence the Australians succeeded in taking the trenches that ringed the south of the village.

A second attack saw the Australians advance to the edge of the village.

A third attack brought them to the Albert-Bapaume Road that runs through the village. The Germans retreated to the eastern end of the village where they had deep dugouts and machine gun nests.

Gibraltar Bunker 1916

By this time the ridge was heavily cratered and orientation was difficult. The Australians consolidated the village including taking Gibralter Bunker but were unable to push up to the eastern edge of the village.

Gibraltar Bunker today

In the ensuing days German artillery pounded the village determined to oust the Australians. the Australians appealed for a counter barrage. In addition to the batteries of I Anzac and II Corp the guns of two British corps joined in.

The Australians suffered nearly 5,300 casualties getting a foothold in Pozières.

Site of the Windmill, Pozières

On 27th July the 2nd Australian Division relieved the 1st and were subjected to continual heavy bombardment while they prepared the attack on the German lines which now lay across the Albert-Bapaume Road at the eastern end of the village on the site of the old windmill. The main attack commenced on 29th July. As the Australians approached the German line they were met by a hail of machine gun fire and encountered uncut barbed wire. The attack faltered at a cost of 3,500 casualties.

The next attack was planned for 9:15 pm so that the remains of the windmill would be visible on the ridge helping orientation. Under heavy shelling a series of trenches were dug to approach the windmill. Finally on 4th August the site was captured and the following night the 4th Australian Division took over the position.

Albert Jacka VC

A subsequent counter attack was repulsed, due in part to the efforts of Lt Albert Jacka who had won a VC at Gallipoli, and Pozières was secure. The taking of the windmill cost Australia 6,850 casualties.

Mouquet Farm, Pozières

The next target on the Pozières ridge was Mouquet Farm, known to the troops as “Moo Cow Farm” or “Mucky Farm”. The fighting here began on 10th August 1916 and Australian troops established advance posts in the valley south of the farmland to the east. Attacks were then made to the north east in an attempt to deepen the salient by the farm. By the 22nd August after several more attacks it became clear that the main German defensive position was underground, where the Germans had excavated the cellars to create linked dug outs. On 3rd September the 4th Australian Division attacked again and initially captured much of the surface of the farmland and nearby trenches. However German counter attacks pushed them back.

The approaches to the farm along the ridge were visible to German artillery spotters and attacking forces were subject to heavy bombardments. Three subsequent attacks at the end of August and into September failed before the Australians were relieved by the Canadians on 5th September.

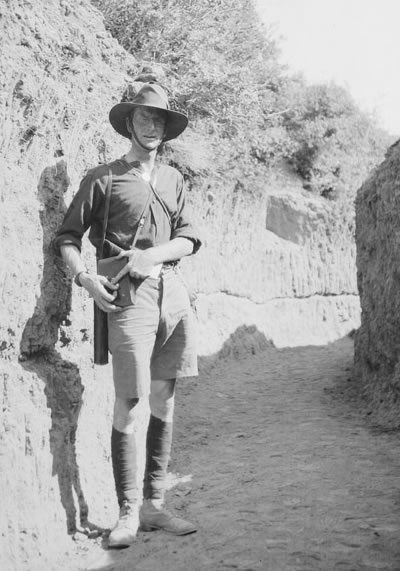

Charles Bean

It is no wonder that Charles Bean, the Australian official historian described the Pozières Ridge as “more deeply sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth.”

Australian National Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux

On 24th April 1918 two German Divisions supported by 15 tanks captured Villers-Bretonneux and drove the British lines back by three kilometres. By the end of the day the Germans had created a bulge in the line and were well placed to attack hill 104 on the ridge behind Villers-Bretonneux. If the Germans captured Hill 104 they would be able to directly shell Amiens, which was not only a major town but also the main railway hub for the area. Two Australian brigades , with British support, counterattacked during the night and succeeded in reclaiming much of the land lost. But at first light the Germans were still in possession of Villers-Bretonneux and a salient connecting their line to D’Arquenne Wood. After a pause to reorganise the Australians and the British troops sealed off the town, then recaptured it. Within 48 hours of the initial attack the front line had returned close to its former position.

The Sir John Monash Centre opened behind the Australian National Memorial in 2018. It is a largely audio-visual centre that draws on Australia’s extensive archives to tell the story of “ordinary” Australians on the Western Front. It is rare to find so much readily accessible information, superbly displayed, in one place.

Original Grave of the Unknown Soldier, Adelaide Cemetery

In 1993 an unknown Australian soldier was exhumed from Adelaide Cemetery close to Villers-Bretonneux and returned to Australia.

After lying in state in King’s Hall in Old Parliament House the unknown soldier was interred in the Hall of Memory at the Memorial in Canberra. He was buried with a bayonet and a sprig of wattle in a Tasmanian blackwood coffin, and soil from the Pozières battlefield was scattered in his tomb.

Museum over the school, Villers-Bretonneux

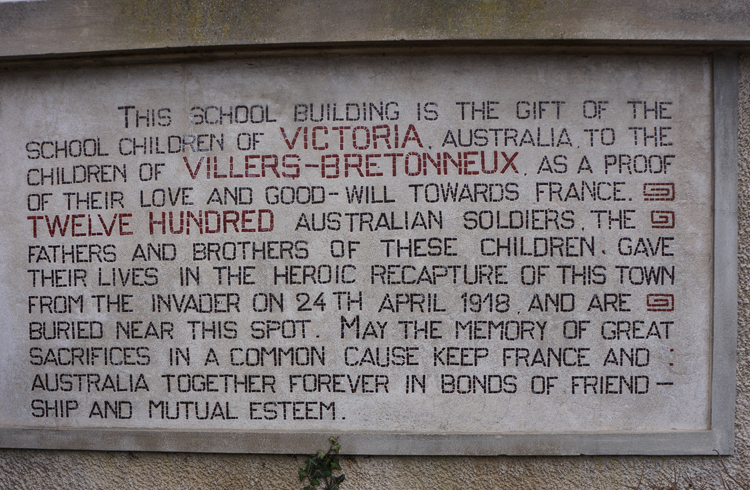

After the war Australians paid to help rebuild the village and to this day the links between Villers-Bretonneux and Australia are strong. Each ANZAC Day the village plays host to thousands of Australians who attend the dawn service at the Australian national Memorial here.

Plaque at Victoria School, Villers-Bretonneux

Victoria School, built in 1923-27, was a gift from the children of Victoria to the children of Villers-Bretonneux. In Victoria Hall and in every schoolroom is the inscription “N’oublions jamais l’Australie” i.e. “Let Us Never Forget Australia”.

Following the Black Saturday bush fires in 2009, the school children from Villers-Bretonneux raised $21 000 for the Victorian bushfire appeal. In 2019/20 the appeal has been repeated raising over $37,000 for the Robinvale Fire Department. SEE NEWS PAGE.

Australian Corp Memorial, above Le Hamel

The Battle of Hamel on 4th July 1918 was the first battle in which the Australian Corps was commanded by an Australian General, Lieutenant General Sir John Monash. An engineer before the war, Monash embraced technology and realised that the key to a successful attack was mobility. He made great efforts to ensure that tanks, infantry, artillery, aircraft and signallers all worked together. 8,000 Australians and 1,000 Americans, under Monash’s command, attacked Le Hamel. In an hour and a half they had taken all their objectives including the village of Le Hamel and the ridge on which the Australian Corps Memorial now stands.